On 26 April 1986, a routine safety test at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Soviet Ukraine spiraled into the worst nuclear disaster in history. The explosion of Reactor 4 released massive amounts of radiation across Europe, reshaping global attitudes toward nuclear power. This article explores how the catastrophe unfolded, its human cost, and its long-lasting environmental and political impact.

The Night of the Explosion: How the Chernobyl Disaster Unfolded

The Chernobyl disaster began with a combination of flawed reactor design, inadequate safety culture, and human error. The plant used an RBMK-type reactor, a Soviet design that was powerful but inherently unstable under certain conditions and lacked a robust containment structure. On the night of the accident, engineers prepared to run a safety test to determine how long turbines would keep generating electricity after a power loss.

To conduct this test, operators disabled key safety systems and violated standard procedures. The reactor was brought to an unusually low power level, which made it unstable. In an effort to raise power, control rods were withdrawn beyond prescribed limits, and automatic shutdown mechanisms were suppressed. The reactor’s positive void coefficient—where steam formation increases reactivity—created a dangerous feedback loop.

At 1:23 a.m., a surge in power occurred when operators initiated the test and then attempted an emergency shutdown. Design flaws in the control rods caused a sudden spike in reactivity instead of damping it. A massive steam explosion blew the 1,000-ton reactor lid off, followed by a second explosion that scattered radioactive fuel and graphite onto the roof and surrounding area.

Almost immediately, fires broke out, especially in the graphite moderator, which burned intensely and propelled radioactive particles into the atmosphere. Firefighters, unaware of the true nature of the disaster, rushed to the scene with minimal protective gear. Many received lethal doses of radiation within minutes or hours, becoming among the first victims of the catastrophe.

In the nearby city of Pripyat, home to about 50,000 people, life initially continued as normal. Residents were not informed of the scale of the accident. Children went to school, weddings took place, and people watched the strange glow from the reactor, unaware it was deadly. By the next day, rising radiation levels and reports of acute sickness among workers forced authorities to act. Buses arrived, and within 36 hours of the explosion, Pripyat was fully evacuated, its residents told they would be gone for only a few days. They never returned.

As radioactive plumes rose higher, winds carried contamination across vast areas of the Soviet Union and Europe. Sweden first detected abnormal radiation levels on 28 April, pressuring the Soviet government to admit something had gone terribly wrong. What began as a local industrial accident had now become an international crisis.

Human, Environmental, and Political Fallout

The human toll of Chernobyl unfolded over days, years, and decades. In the immediate aftermath, plant workers and first responders suffered acute radiation syndrome (ARS). Dozens died within weeks, while thousands more would endure long-term health consequences. Doctors and nurses treated patients without fully understanding the scale of exposure; some medical staff themselves received dangerous doses.

The Soviet government mobilized an enormous cleanup effort involving hundreds of thousands of “liquidators”: soldiers, firefighters, engineers, and volunteers who decontaminated buildings, buried radioactive topsoil, cut down forests, and constructed a concrete “sarcophagus” over the destroyed reactor. Many liquidators worked in brief shifts to limit exposure, some for only seconds on the reactor roof, yet many later reported chronic health problems, including cancers and cardiovascular disease.

Children in contaminated regions of Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia were particularly vulnerable. A sharp increase in thyroid cancer, especially among those exposed to radioactive iodine through milk and local food, was documented in the ensuing years. While exact numbers remain contested, the World Health Organization and other agencies agree that Chernobyl significantly increased cancer risks for those in heavily contaminated zones.

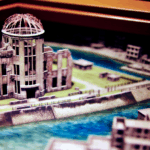

The environmental impact was equally staggering. A heavily irradiated area around the plant, now known as the *Chernobyl Exclusion Zone*, was evacuated and remains largely uninhabited by civilians. Forests absorbed much of the fallout; one nearby stand of trees, killed by intense radiation, turned a reddish color and became infamous as the “Red Forest.” Soil, water, and wildlife were contaminated, and radionuclides such as cesium-137 and strontium-90 entered local ecosystems.

Over time, nature adapted in surprising ways. With humans absent from much of the Exclusion Zone, wildlife populations rebounded: wolves, boars, deer, and even rare species like Przewalski’s horses flourished. Yet this apparent “rewilding” exists alongside genetic mutations, reduced lifespans in some species, and complex ecological changes that scientists continue to study. Chernobyl became an unintended, vast laboratory for understanding radiation’s long-term effects on living systems.

The political fallout reverberated across the Soviet Union and beyond. Initially, Soviet authorities tried to limit information, following a tradition of secrecy. But international detection of radiation and growing domestic concern forced a partial acknowledgement of the disaster. The state’s reluctance to inform and protect its citizens fueled distrust and undercut public faith in the government.

Chernobyl played a crucial role in advancing *glasnost* (openness), a policy championed by Mikhail Gorbachev. The disaster exposed the costs of bureaucratic opacity and technological overconfidence, and it contributed to growing calls for transparency and reform. Many historians see Chernobyl as one of the events that eroded the legitimacy of the Soviet state, hastening its eventual collapse in 1991.

Globally, the disaster reshaped attitudes toward nuclear energy. Many countries tightened safety standards, redesigned reactors, and improved emergency protocols. Some halted or slowed nuclear programs, while public opinion turned sharply skeptical in many regions. International frameworks for nuclear safety and early warning were strengthened, reflecting a recognition that nuclear accidents do not respect borders.

Even decades later, Chernobyl remains a potent symbol in culture and memory. Documentaries, books, and dramatizations have explored not only the technical causes but also the human stories: families uprooted, liquidators’ sacrifices, and communities left behind. The site has become a dark tourism destination, with guided visits to the ghost city of Pripyat, decaying amusement parks, and the looming New Safe Confinement arch over Reactor 4, completed in the 2010s to replace the deteriorating original sarcophagus.

Legacy and Lessons

The long-term legacy of Chernobyl lies in what it revealed about technology, power, and human responsibility. It showed that cutting-edge systems can fail catastrophically if design flaws, cost-cutting, and secrecy intersect. It highlighted the need for clear communication in crises, robust safety cultures, and international cooperation when managing technologies that can impact the entire planet.

Today, as debates about energy, climate change, and nuclear power continue, Chernobyl serves as both a warning and a lesson. It underscores that while nuclear energy can reduce carbon emissions, it demands rigorous oversight, transparency, and preparedness for the worst-case scenario. The ruins of Reactor 4 stand as a stark reminder of what happens when those obligations are neglected.

Conclusion

The Chernobyl disaster was more than a single explosion; it was a turning point in modern history. From the fatal errors of a late-night test to the long struggle of liquidators, evacuees, and affected communities, its consequences spanned human health, the environment, politics, and global energy policy. Remembering Chernobyl means recognizing the risks embedded in powerful technologies—and the enduring responsibility to manage them with honesty, respect, and care.